Background

Corneal opacity is the fifth leading cause of blindness worldwide¹. A common cause of corneal opacity is infectious keratitis. In developed countries, contact lenses are the leading cause of infectious keratitis while in developing countries it is from corneal trauma during agriculture work¹. The most common organism responsible for microbial keratitis in contact lens wear is Pseudomonas aeruginosa². When the visual axis is involved, a cornea transplant may be required to improve vision. Corneal transplants have a higher rate of rejection in younger patients³.

Case Description

A 19-year-old Hispanic female presented for a gas permeable contact lens fitting. Her ocular history was remarkable for microbial keratitis OS caused by Pseudomonas following extended wear of an unknown monthly soft contact lens.

Entering visual acuities were 20/20 OD with correction and 20/200 OS without correction which improved to 20/40 with pinhole. All other entrance testing was unremarkable.

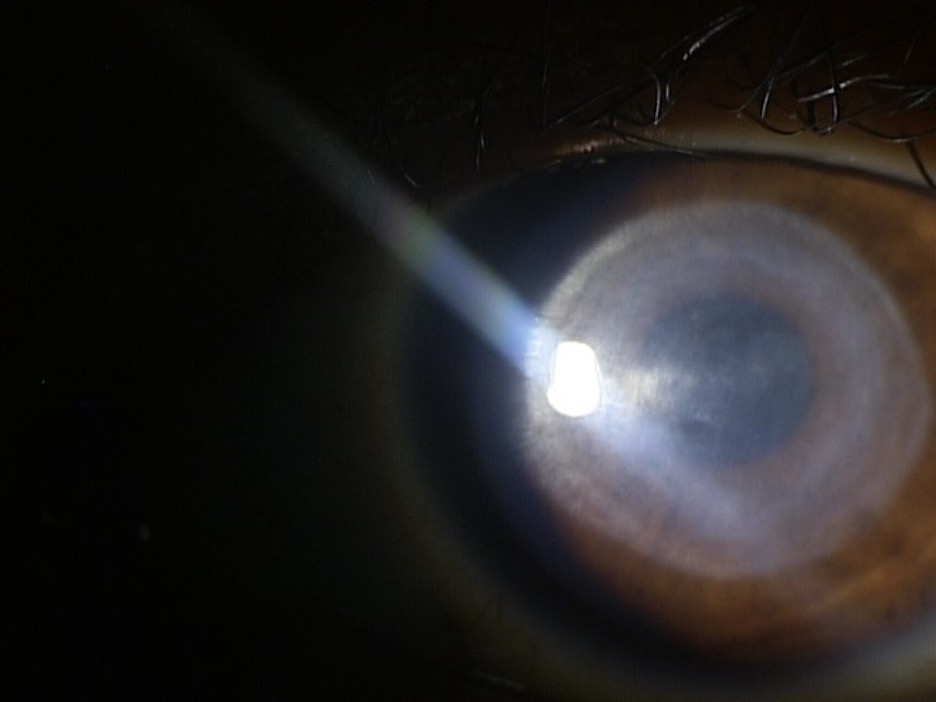

Slit lamp examination revealed a 6 mm round, central stromal scar with significant stromal thinning OS (Figure 1).

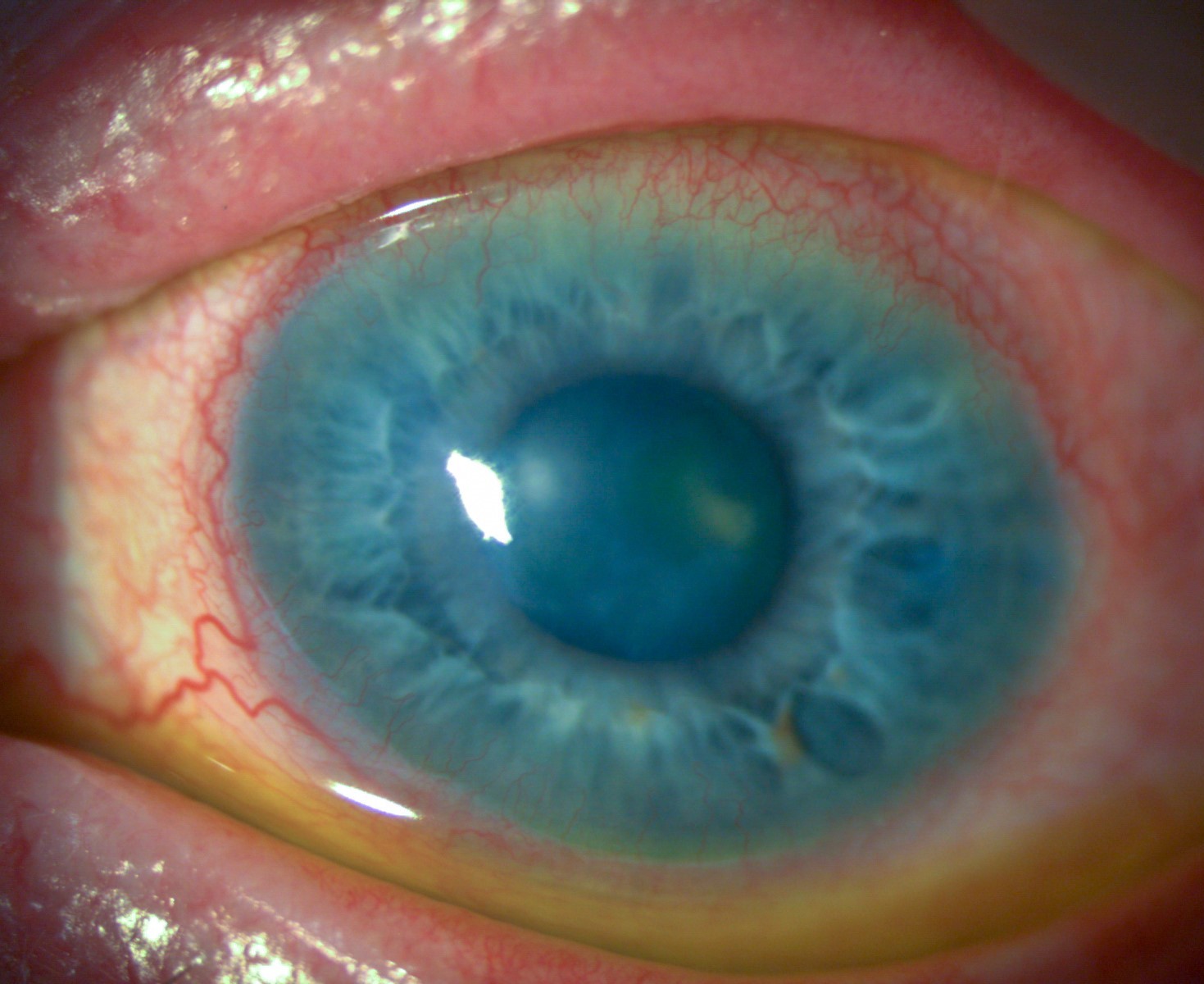

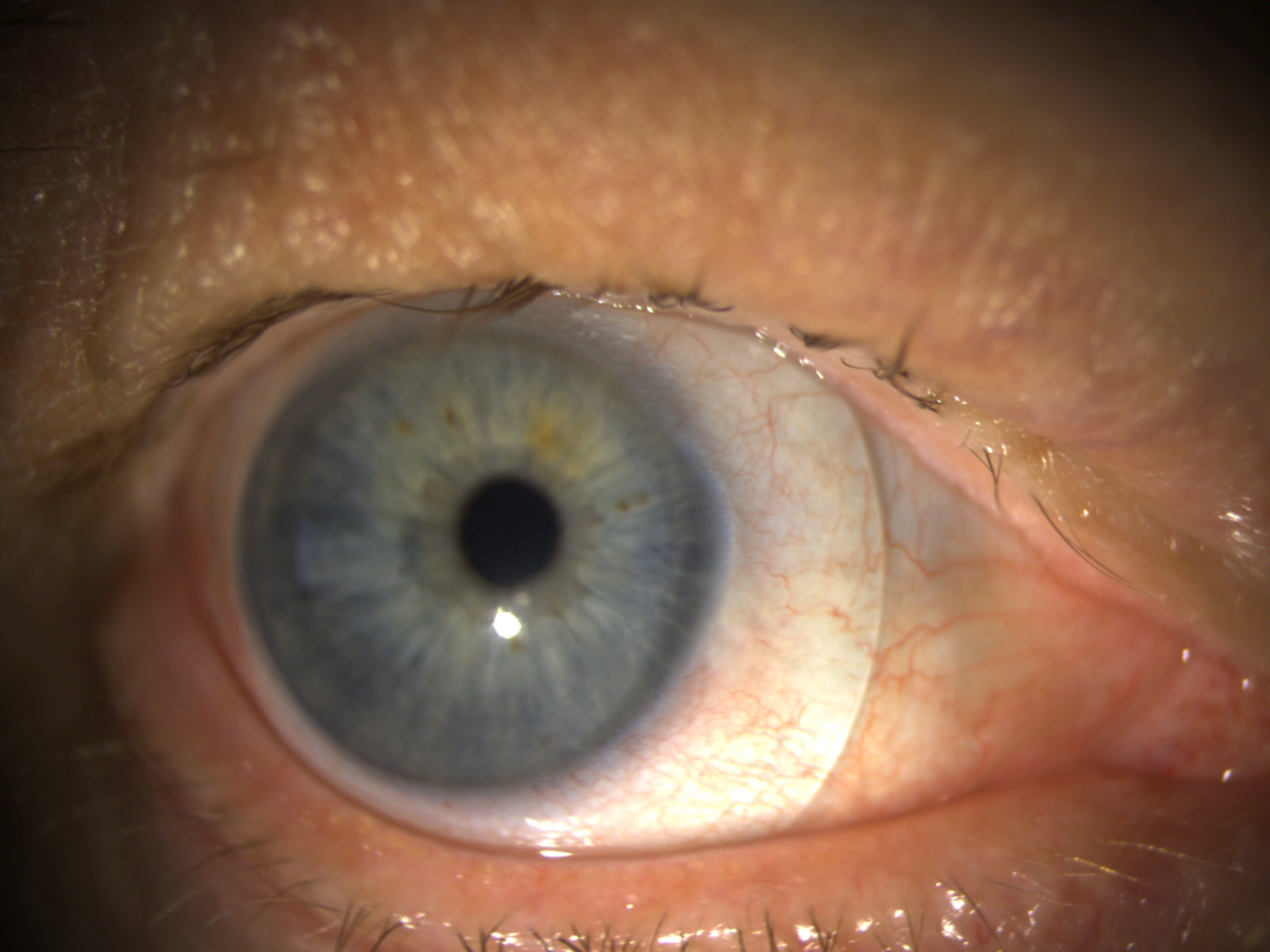

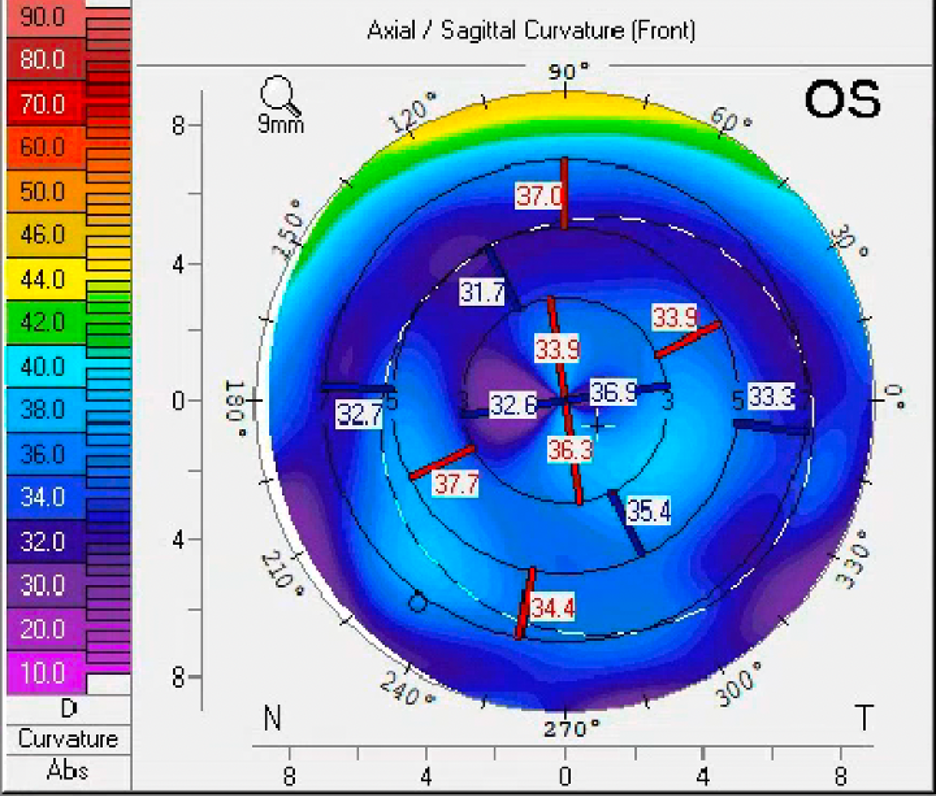

Simulated keratometry measurements were taken from tomography and were 40.75/43.0 @ 89 OD (Figure 2), 33.75/35.50 @ 99 OS (Figure 3).

Manifest Refraction was -7.00-1.50×170 OD with a distance acuity of 20/20 and +2.00 sphere OS with a distance acuity of 20/80.

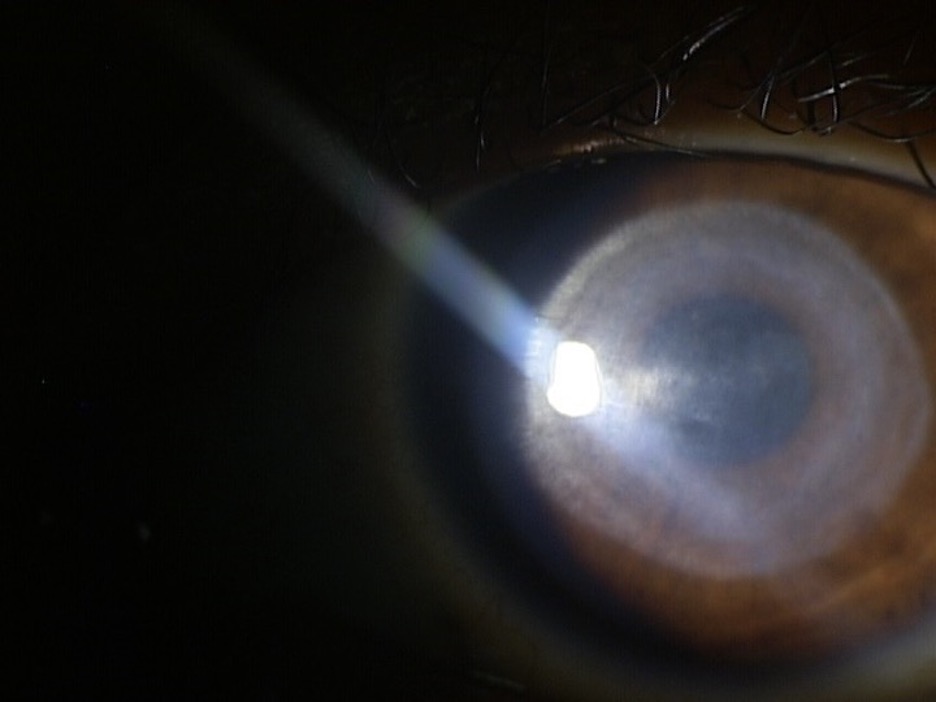

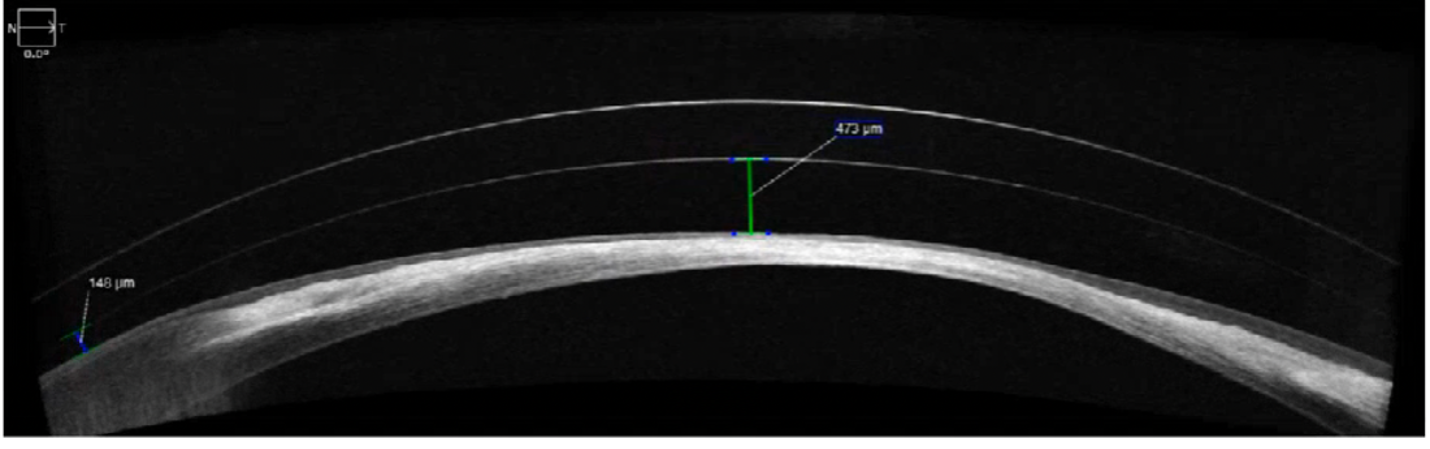

Due to the decrease in VA secondary to a central corneal opacity a diagnostic scleral lens was applied to the left eye to determine visual potential. The initial diagnostic lens that was applied to OS was a prolate lens (Table 1A) that showed excessive central fluid reservoir clearance (Figure 4A). Her VA improved to 20/30 with an over-refraction. Since there was a vast improvement in VA with a scleral lens, the decision was made to peruse wearing a scleral lens OS. The final lens order was changed to an oblate design (Table 1B) which improved the central fluid reservoir clearance (Figure 4B).

Optimum Extreme, a high-DK material was selected to allow the compromised cornea to receive as much oxygen as possible while she was wearing the lens. Since the initial corneal insult happened because of non-compliance, the importance of contact lens hygiene, wearing schedule, cleaning regimen and proper filling solution was discussed at length with her and her parents.

She was closely followed over the first three months of scleral lens wear to ensure appropriate wear.

Figure 1: Slit lamp photo showing a 6mm round central stromal scar OS secondary to microbial keratitis.

Figure 2: Axial map showing with-the-rule astigmatism in the right eye.

Figure 4A: An AS-OCT of a prolate diagnostic scleral lens OS showing excessive central vault with adequate mid-peripheral vault.

Figure 3: Axial map showing central corneal flattening secondary to microbial keratitis in the left eye.

Figure 4B: An AS-OCT of an oblate scleral lens design OS showing adequate central clearance after ~6 hours of wear.

| Type | Power | BC | Diameter | Edge | Design |

| Onefit 2.0 | Plano | 8.4 | 14.9 | std | Prolate |

Table 1A. Initial diagnostic scleral lens OS that showed excessive central clearance

| Type | Power | BC | Diameter | Edge | Design | Material |

| Onefit 2.0 | +6.50 | 8.4 | 14.9 | std | Oblate – CCR 230 | Optimum Extreme |

Table 1B. Final scleral lens design OS

Conclusions

Corneal scarring after microbial keratitis leads to vision loss secondary to corneal opacity and irregular astigmatism⁴. The two most common options to improve vision in these cases are corneal transplantation or a specialty contact lens. Corneal gas permeable or scleral contact lenses should be considered if they are able to provide the patient with functional vision as was demonstrated in this case.