With the increasing use of corneal cross-linking (CXL) for keratoconus, some have questioned whether this treatment could reduce the demand for specialised contact lenses.

Keratoconus is a well-known condition among practitioners that fit speciality contact lenses. This progressive disorder affects approximately 1 in 500 individuals and is much more common than previously assumed .1,2 The severity of this corneal ectasia varies, often presenting asymmetrically between the eyes.3 It is characterised by corneal thinning, reduced best-corrected visual acuity and significant refractive changes over a short period of time. Eventually, irregularity in corneal shape leads to visual distortions that cannot always be corrected with conventional optical aids such as glasses or soft contact lenses.3

This is where speciality contact lenses, particularly rigid gas-permeable (RGP) lenses of different designs, play a crucial role. These lenses create a smooth refractive surface, compensating for corneal irregularities. This reduces higher-order aberrations and often restores functional vision where other methods, such as glasses and soft lenses, fail.4 As a result, speciality contact lenses are often the only viable solution for many keratoconus patients, enabling them to function effectively in both their professional and personal lives. But why would we be content with smacking a RGP lens on an unstable cornea? Contact lenses do not treat the underlying condition, meaning that corneal irregularity can continue to worsen, potentially reaching the point where a transplant is required.

Let’s start by fixing the roof!

Removal of a patient’s epithelium with an Amoils brush prior to CXL treatment

So now that the roof is fixed. What about the furniture?

Modern scleral lenses are highly tuneable to wearers needs, making them ideal for keratoconic eyes

Could CXL fully replace contact lenses for keratoconic patients?

Let us, just for a moment, play with the idea that we would truly try to use CXL to undermine the speciality contact lens industry. To achieve this, we would firstly need to screen every 10-15-year-old across the globe using advanced and costly Scheimpflug technology. Upon diagnosis, we would have to CXL treat each and every one of them, ensuring that progression of keratoconus is halted before it could ever lead to the need for specialised lenses. Ethical considerations relating to age and the risk of complications would also have to be considered. Doesn’t sound very realistic, does it?

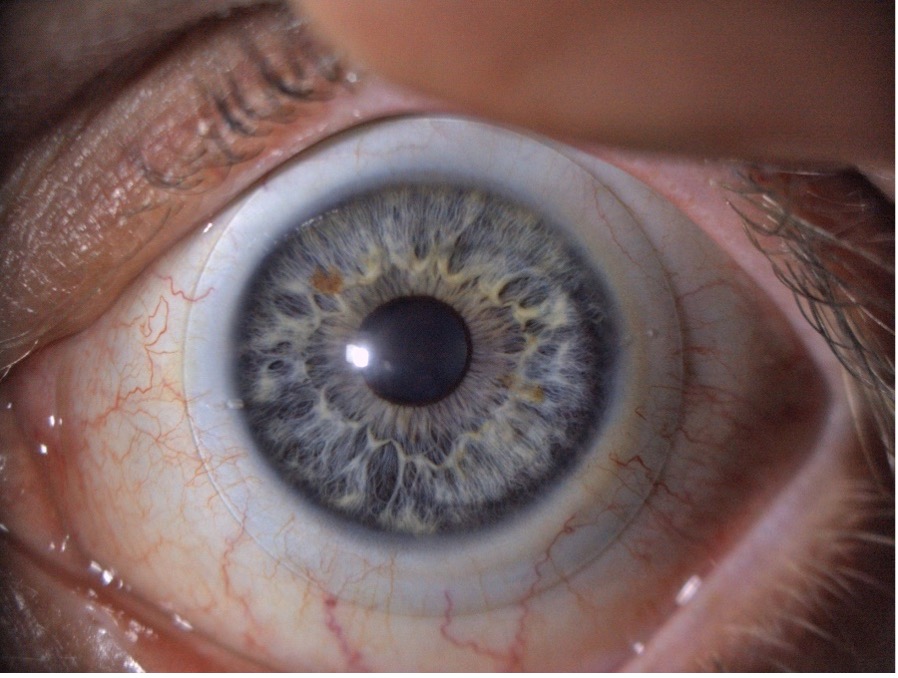

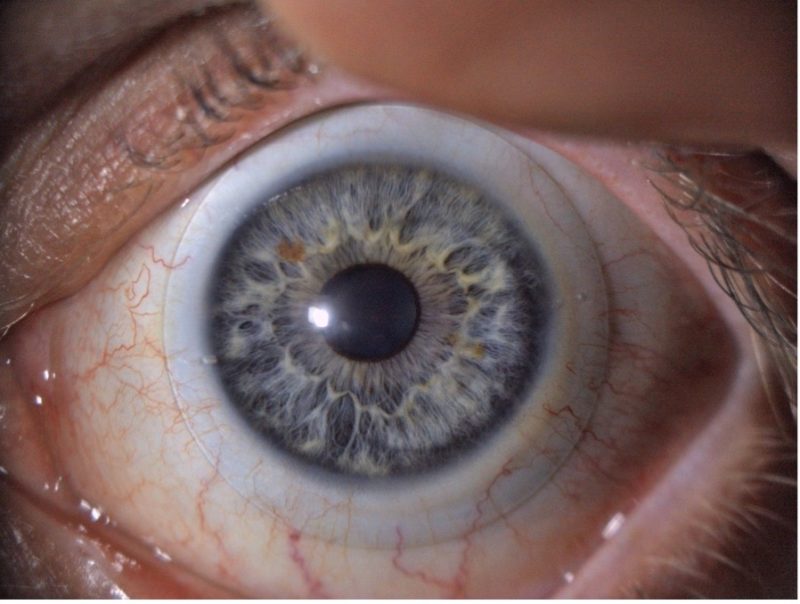

A keratoconic eye with scleral lens in place

Conclusion: We must address the fundamental clinical challenges while simultaneously optimising visual outcomes

Effective management of keratoconus is not just about halting disease progression but also about ensuring that patients achieve the best possible vision. CXL plays a crucial role in stabilising the cornea, but it does not eliminate the need for precise optical correction. In fact, one could argue that without the rapid advancements in specialised contact lenses, CXL would not have been the success it is today. By combining structural stabilisation with advanced visual rehabilitation, we move beyond simply managing the disease, we actively enhance the patient’s quality of life. Because what is the point of fixing the roof only to live in a house without furniture?